Extrema of Functions – Lecture 6

Topic: Fermat’s Theorem. A Necessary Condition for the Existence of an Extremum of a Function.

Summary

To analyze the behavior of a function ![]() , we often use its derivative

, we often use its derivative ![]() . In this lecture, I will present and prove Fermat’s Theorem, which gives a necessary condition for the existence of an extremum of a function at a point by referring to its derivative. I will also show that this condition is not sufficient—using examples of points where it is satisfied, yet no extrema occur there…

. In this lecture, I will present and prove Fermat’s Theorem, which gives a necessary condition for the existence of an extremum of a function at a point by referring to its derivative. I will also show that this condition is not sufficient—using examples of points where it is satisfied, yet no extrema occur there…

Fermat’s Theorem (a necessary condition for the existence of a function’s extremum at a point)

Let the function f(x) be defined on an interval [a, b] and attain an extremum (a maximum or a minimum) at an interior point x0 of this interval. If the (finite) derivative f′(x0) exists at that point, then certainly:

f′(x0) = 0

In other words: if a function has an extremum at a point and it has a derivative at that point, then for sure—absolutely for sure—the derivative of the function at that point is equal to zero.

Let us immediately note (we will return to this later) that Fermat’s Theorem does not work “the other way around,” meaning that from the fact that the derivative of a function at a point equals zero it does not follow that the function attains an extremum at that point.

So, once again (simplifying): if we have an extremum, then we have a derivative equal to zero.

To prove Fermat’s Theorem, I will first introduce and prove a lemma (about monotonicity of a function depending on its derivative), which is useful not only for this proof:

Lemma on the Monotonicity of a Function

Let the function f(x) have a finite derivative at the point x0.

If the derivative at this point is positive, then the function f(x) is increasing at that point.

If the derivative at this point is negative, then the function f(x) is decreasing at that point.

The lemma expresses a well-known and widely used relationship between the behavior of a function and its derivative.

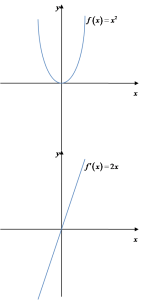

For example, take the function ![]() and its derivative

and its derivative ![]() . Let us draw their graphs one under another:

. Let us draw their graphs one under another:

We can see that the function ![]() is increasing/decreasing on the same intervals where its derivative

is increasing/decreasing on the same intervals where its derivative ![]() takes values greater/less than zero.

takes values greater/less than zero.

The lemma is also very easy to “feel” intuitively: since the derivative at a point expresses the change in the function value for an infinitely small change of the argument, if the derivative is positive, then this change must also be positive (the function must “go up”)—and vice versa: the function is increasing.

If the derivative is negative, the values must “go down”—the function is decreasing.

We will now move on to a rigorous proof of the lemma. To do this, we must recall (from high school) what it means, by definition, that a function is “increasing” at a point and what it means that it is “decreasing” at a point.

Definition of a Function Increasing at a Point

Definition of a Function Increasing at a Point

A function f(x) is said to be increasing at the point x0 if there exists a right-hand neighborhood of x0 such that for every x from this neighborhood: f(x0) > f(x), and there exists a left-hand neighborhood of x0 such that for every x from this neighborhood: f(x) < f(x0).

Definition of a Function Decreasing at a Point

A function f(x) is said to be decreasing at the point x0 if there exists a right-hand neighborhood of x0 such that for every x from this neighborhood: f(x) < f(x0), and there exists a left-hand neighborhood of x0 such that for every x from this neighborhood: f(x0) > f(x).

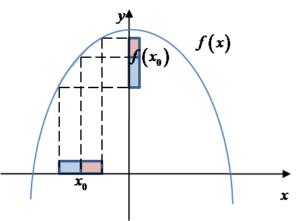

Let us see how this definition of an increasing function at a point “works” on a graph:

From the graph we can see that the function is increasing at the point ![]() . It is increasing because there exists a right-hand neighborhood of the point

. It is increasing because there exists a right-hand neighborhood of the point ![]() (marked in red on the x-axis), and for x-values from that neighborhood the corresponding values (marked in red on the y-axis) are greater than the value of the function at the point

(marked in red on the x-axis), and for x-values from that neighborhood the corresponding values (marked in red on the y-axis) are greater than the value of the function at the point ![]() (i.e., f\left( {{x}_{0}} \right)>f\left( x \right)). And there also exists a left-hand neighborhood of the point

(i.e., f\left( {{x}_{0}} \right)>f\left( x \right)). And there also exists a left-hand neighborhood of the point ![]() (marked in blue on the x-axis), and for x-values from that neighborhood the corresponding values (marked in blue on the y-axis) are smaller than the value of the function at the point

(marked in blue on the x-axis), and for x-values from that neighborhood the corresponding values (marked in blue on the y-axis) are smaller than the value of the function at the point ![]() (i.e.,

(i.e., ![]() ).

).

Now that we know what “increasing at a point” and “decreasing at a point” mean precisely, we can proceed to the proof of the lemma:

Proof of the Lemma on the Monotonicity of a Function

The proof of the lemma is simple and relies directly on the definition of the derivative of a function at a point. If, by assumption, the derivative of the function at the point x0 is greater than zero (f′(x0) > 0) and by definition the derivative is equal to (see previous Lecture):

f′(x0) = limΔx→0 ( f(x0 + Δx) − f(x0) ) / Δx

this means that, by assumption:

limΔx→0 ( f(x0 + Δx) − f(x0) ) / Δx > 0

Since this inequality holds, it follows that for certain sufficiently small values of Δx we have:

( f(x0 + Δx) − f(x0) ) / Δx > 0

If we additionally assume that Δx is positive (it tends to zero but remains positive) and multiply both sides by Δx, we obtain:

f(x0 + Δx) − f(x0) > 0

That is:

f(x0) < f(x0 + Δx)

Thus, I have shown that for a certain right-hand neighborhood of x0 (since Δx was positive, we increased x0), the values of the function at x0 are smaller than the values of the function for x from that right-hand neighborhood.

On the other hand, if we assume that the increment Δx is negative (but still tending to zero), after multiplying the inequality

( f(x0 + Δx) − f(x0) ) / Δx > 0

by a negative value (which changes the sign), we obtain:

f(x0 + Δx) − f(x0) < 0

That is:

f(x0) > f(x0 + Δx)

Thus, I have shown that in a sufficiently small left-hand neighborhood of x0 (that is, x0 increased by a negative increment Δx— in other words, decreased), the value of the function at x0 is greater than the values of the function in that neighborhood.

In this way, I have proved the first part of our lemma:

Lemma on the Monotonicity of a Function

Let the function f(x) have a finite derivative at the point x0.

If the derivative at this point is positive, then the function f(x) is increasing at that point.

Since the inequalities I derived mean nothing more and nothing less than that the function is increasing at the point (according to the definition).

The proof of the second part proceeds in a completely analogous way.

END OF THE PROOF OF THE LEMMA ON THE MONOTONICITY OF A FUNCTION

With the lemma on monotonicity of a function proved, the proof of Fermat’s Theorem becomes child’s play:

Proof of Fermat’s Theorem

If (according to the assumptions of the theorem) the function f(x) attains an extremum at some point x0 and has a derivative there, then:

1. If the value of this derivative is positive (f′(x0) > 0), then according to the lemma on the monotonicity of a function, the function is increasing at that point.

If the function is increasing at that point, it cannot attain an extremum there. Indeed — if its values are greater than the value to the left of x0 and smaller than the value to the right of x0, then there certainly does not exist any neighborhood of x0 in which the function value at x0 is the greatest or the smallest — and that is how we defined extrema in the previous lecture.

Put more simply: if the function is increasing at a point, it will always be greater than something and smaller than something else, whereas according to the definition of an extremum it should always be either greater (maximum) or always smaller (minimum).

Therefore, the value of the derivative at x0 cannot be positive.

2. If the value of the derivative is negative (f′(x0) < 0), then according to the lemma on the monotonicity of a function, the function is decreasing at that point.

Fermat’s Theorem as a Necessary but Not Sufficient Condition for an Extremum of a Function at a Point

We should stress once again that the necessary condition for the existence of an extremum works like this:

IF: the function has an extremum at the point ![]() and it has a derivative at the point

and it has a derivative at the point ![]()

THEN: the derivative of the function at the point ![]() equals 0.

equals 0.

However, it does not work like this:

IF: the derivative of the function at the point ![]() equals 0

equals 0

THEN: the function has an extremum at the point ![]() .

.

This is important. In practice, it means that to show a function attains an extremum at a point, it is not enough to check whether its derivative at that point equals zero.

Example

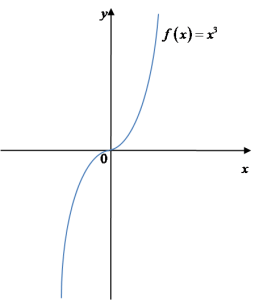

Consider the function ![]() . Its derivative is

. Its derivative is ![]() . The derivative at the point

. The derivative at the point ![]() is indeed equal to 0 (because

is indeed equal to 0 (because ![]() ), but as we can see from the graph, there is no extremum there…

), but as we can see from the graph, there is no extremum there…

Other situations are also possible. For example, the function ![]() at the point

at the point ![]() does not have a derivative at all (I showed such cases in the lectures on derivatives)—and yet it does have an extremum (just draw it and you will see).

does not have a derivative at all (I showed such cases in the lectures on derivatives)—and yet it does have an extremum (just draw it and you will see).

So we can see that Fermat’s Theorem alone is not enough for us to determine extrema of functions…

THE END

While writing this post, I used:

1. “Differential and Integral Calculus. Vol. I.” G.M. Fichtenholz. 1966 edition.

Click here to review what extrema of a function are (previous Lecture) <–

Click to return to the page with lectures on analyzing functions