Derivatives of Functions Lecture 3

Topic: One-sided derivatives. Infinite derivatives.

Summary

In this lecture I will show what one-sided derivatives of a function are, as well as its infinite derivatives. We will also see how to prove that the derivative of a function does not exist.

One-sided derivatives of a function

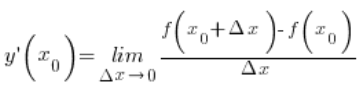

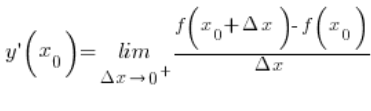

When defining derivatives (regardless of whether in the way described in Lecture 1 or in Lecture 2), we arrived at the conclusion that the derivative of a function at the point ![]() is a certain kind of limit of a function:

is a certain kind of limit of a function:

We obtained this limit…

1. In the first lecture by calculating increasingly precise average velocities for time increments closer and closer to ![]() . In the example from the lecture these were average velocities between 2 and 2.5 seconds of motion, then between 2 and 2.25 seconds, between 2 and 2.1 seconds, etc. So we were increasing

. In the example from the lecture these were average velocities between 2 and 2.5 seconds of motion, then between 2 and 2.25 seconds, between 2 and 2.1 seconds, etc. So we were increasing ![]() by increments

by increments ![]() and letting those increments tend to zero. Nothing prevented us from taking average velocities between 1.5 and 2 seconds, 1.75 and 2 seconds, 1.9 and 2 seconds, etc., so we would decrease

and letting those increments tend to zero. Nothing prevented us from taking average velocities between 1.5 and 2 seconds, 1.75 and 2 seconds, 1.9 and 2 seconds, etc., so we would decrease ![]() by increments

by increments ![]() and let those increments tend to zero.

and let those increments tend to zero.

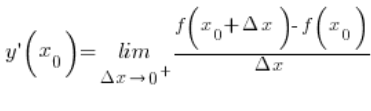

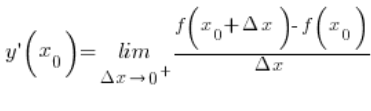

The derivative obtained as the result of approaching ![]() from the right side can be called the right-hand derivative of the function and denoted as:

from the right side can be called the right-hand derivative of the function and denoted as:

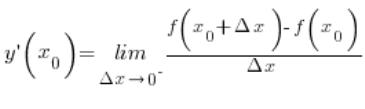

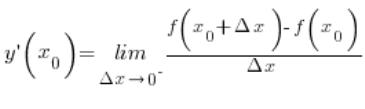

The derivative obtained as the result of approaching ![]() from the left side can be called the left-hand derivative of the function and denoted as:

from the left side can be called the left-hand derivative of the function and denoted as:

In our example with Johnny on the sled, both derivatives would be equal (I strongly, strongly recommend taking out a calculator and checking this by computing successive average velocities). However, this is not a rule for all functions and all derivatives. Sometimes, when approaching ![]() from the right side, we obtain a different result (limit) than from the left. Sometimes we can approach only from one side because the function does not exist on the other side… It can vary.

from the right side, we obtain a different result (limit) than from the left. Sometimes we can approach only from one side because the function does not exist on the other side… It can vary.

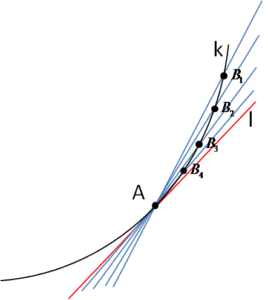

2. In the second lecture we arrived at the derivative by taking successive secants:Notice that in our example, when defining the tangent, I took points ![]() , that is, points approaching A from the right side. By agreeing to take only such points, we obtain positive increments of the arguments

, that is, points approaching A from the right side. By agreeing to take only such points, we obtain positive increments of the arguments ![]() , and the formula for the tangent of the angle of inclination of the tangent line:

, and the formula for the tangent of the angle of inclination of the tangent line:

However, I could just as well take points on the curve approaching A from the left side — in this case the increments ![]() will be negative, and the formula for the corresponding tangent:

will be negative, and the formula for the corresponding tangent:

By taking secants from the left or from the right, we obtain the same (or not) tangent. So we speak of a left-hand tangent and a right-hand tangent. In the case of some functions, these may be two different lines with different tangents of the angle of inclination with respect to the OX axis.

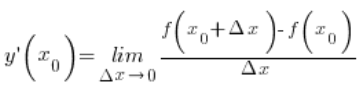

The concept of one-sided derivatives therefore arises quite naturally from the intuitive understanding of what derivatives are. Even if we only knew the definition of the limit of a function at the point ![]() :

:

remembering from lectures on limits that a limit can be left-hand or right-hand, and that it exists when the left-hand and right-hand limits are equal, etc.

Simply forgetting for a moment that this is a derivative and staying purely within the framework of limits of functions, we can compute and understand everything we need about one-sided limits.

One-sided derivatives – when to use them?

After becoming familiar with the above, every student surely feels a certain anxiety — I more or less know what derivatives are, I can more or less compute them, I supposedly have the formulas, and now to learn derivatives I must learn SOMETHING ELSE?

Relax. In practical university calculations, in 99% of cases you will encounter a situation in which the left-hand and right-hand derivatives of a function are equal, and in that case there is no need to introduce analysis of left-hand and right-hand behavior of the limit. The derivative of ![]() is simply at every point

is simply at every point ![]() , there is absolutely no need to even know these subtle distinctions.

, there is absolutely no need to even know these subtle distinctions.

However, one-sided derivatives may be useful to you for two things:

- For a better understanding of what derivatives are (I would not underestimate this)

- For solving certain special types of problems, for example checking whether the derivative at a point exists (and it will exist when the left-hand and right-hand derivatives are equal)

- For more advanced analyses in general

A classic school example for point 2 is:

Example

Check whether the function has a derivative at the point .

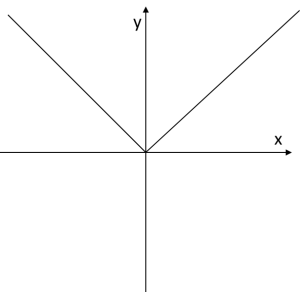

The function ![]() drawn in the coordinate plane would look like this:

drawn in the coordinate plane would look like this:

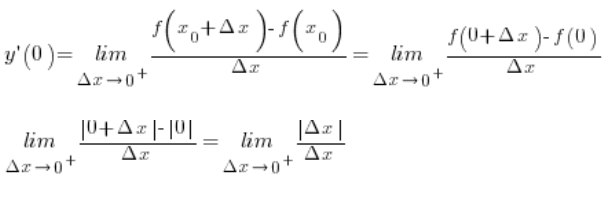

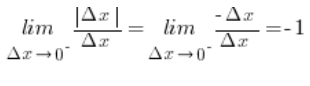

The question is — does it have a derivative at the point ? At first glance — why not? But let us look more closely. We compute the right-hand limit:

Taking :

Now an important moment. ![]() is positive (we know this because we compute the limit as

is positive (we know this because we compute the limit as  ), and the absolute value of a positive number equals that number, therefore:

), and the absolute value of a positive number equals that number, therefore:

The right-hand derivative is therefore equal to 1.

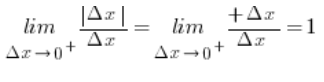

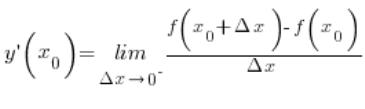

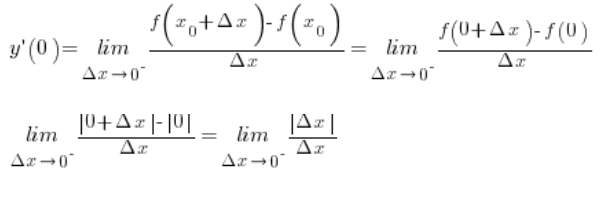

We compute the left-hand limit:

Taking :

Now again an important moment. ![]() is negative (we know this because we compute the limit as

is negative (we know this because we compute the limit as  ), and the absolute value of a negative number equals that number with the minus sign removed (the whole must be positive), therefore:

), and the absolute value of a negative number equals that number with the minus sign removed (the whole must be positive), therefore:

The left-hand derivative is therefore equal to -1.

Thus the left-hand and right-hand derivatives are different. The moral is that the derivative of the function at the point does not exist.

Infinite derivatives

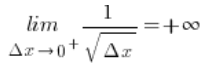

Since — as we already know — the derivative of a function at a point is a certain limit, nothing prevents it from tending to ![]() or

or ![]() — like any proper limit. A derivative obtained in this way can be called an infinite derivative. Of course we can also speak of left-hand and right-hand infinite derivatives (as in the case of any limit). The geometric interpretation of such a limit consists of secants tending to a vertical tangent line (the tangent of

— like any proper limit. A derivative obtained in this way can be called an infinite derivative. Of course we can also speak of left-hand and right-hand infinite derivatives (as in the case of any limit). The geometric interpretation of such a limit consists of secants tending to a vertical tangent line (the tangent of ![]() tends to

tends to ![]() or

or ![]() ).

).

Example

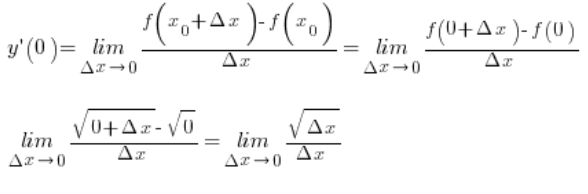

Compute the derivative of the function at the point .

So we need to compute:

In this case it makes no sense to compute the left-hand derivative at ![]() . We cannot take negative

. We cannot take negative ![]() , because real square roots of negative numbers do not exist (let’s not complicate things). Therefore, if a derivative exists at this point, it can only be right-hand, so we have:

, because real square roots of negative numbers do not exist (let’s not complicate things). Therefore, if a derivative exists at this point, it can only be right-hand, so we have:

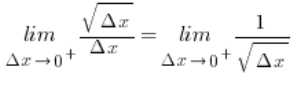

Which tends to plus or minus infinity (limits of functions again, symbol ![]() ), and since both numerator and denominator are positive, it tends to plus infinity.

), and since both numerator and denominator are positive, it tends to plus infinity.

Therefore the function has at the point a right-hand derivative equal to ![]() .

.

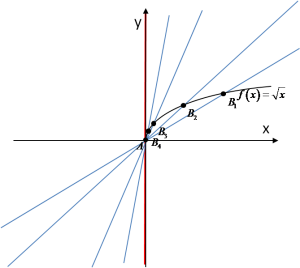

Drawing the graph of the function and taking successive secants…

…we see that the limiting line for these secants is a vertical line with an angle of inclination to the OX axis equal to ![]() .

.

END

While writing this post I used…

1. “Differential and Integral Calculus. Volume I.” G.M. Fichtenholz. Ed. 1966.

Click to recall how to interpret the derivative as a tangent (previous Lecture) <–

Click to see how to use one-sided derivatives of functions in practical problems (next Lecture) –>