Derivatives of Functions Lecture 2

Topic: Derivatives of functions as tangents of the slope of the tangent line

Summary

In the previous lecture we introduced the concept of the derivative of a function as a kind of “velocity” (understanding this word more broadly than just physical speed). In this lecture we will introduce exactly the same thing — namely the derivative of a function — but from a different, more geometric perspective, through the concept of the tangent line.

What is a tangent?

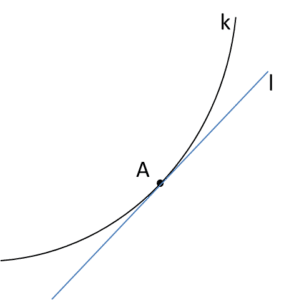

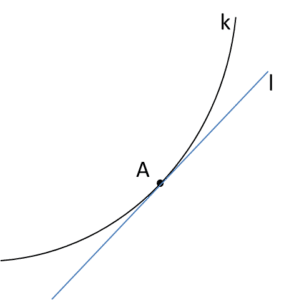

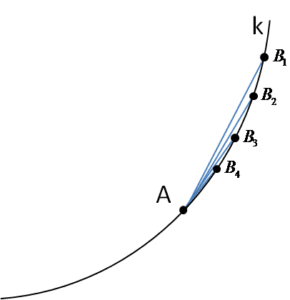

A tangent is like a horse — everyone sees what it is. Every child understands that the tangent to a graph at point A looks more or less like this…

…the problem is how to describe it properly in words and define it. A circular definition: “a tangent is a line that touches” is not enough. Circular definitions contain a logical error — they refer in the definition to the very concept we are trying to define. You cannot define butter as “something that is buttery” — because we do not know what “buttery” means without a definition of butter. Likewise, we cannot use the word “touches” in the definition of a tangent, because we have not yet defined what “touches” actually means.

So maybe like this:

Definition (wrong)

A tangent to a curve at point A is a line that has exactly one common point with the curve, namely point A.

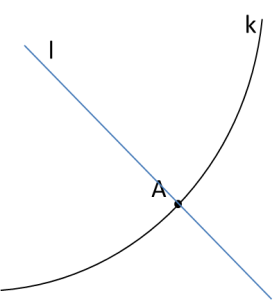

This definition certainly looks better. It matches the tangents to a circle known from high school. But according to it, something like this…

…also represents a tangent to curve k (because it has only one common point A with curve k), and it is also clear that…

…there would be infinitely many such supposed “tangents” to the curve! But is that what we meant? Definitely not. The tangent was supposed to be unique and to look, as a reminder, like this:

Its precise definition (because informally, as I said, we all know what it is) is more complicated than it might seem.

Let’s start with the concept of a chord. We move away from the elementary-school notion of a chord of a circle, generalize the concept, and obtain…

Definition of a chord

A chord is a line segment connecting any two points of a curve.

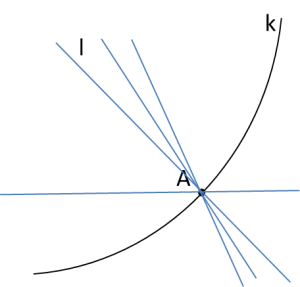

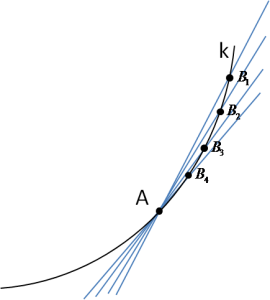

Let’s draw several chords having one endpoint at point A:

Each chord determines a secant:

Definition of a secant

A secant is a line that contains a chord (in other words: a line that intersects a curve at at least two points).

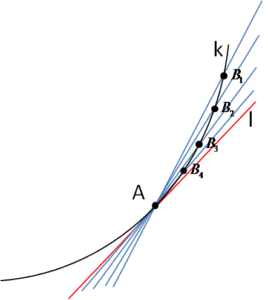

Let us now draw our secants passing through point A:

Now let us notice something important — as the points ![]() approach point A, the corresponding secants more and more resemble our tangent l (marked in red):

approach point A, the corresponding secants more and more resemble our tangent l (marked in red):

This is precisely how the tangent to a curve at point A should be defined: as the limiting line of the secants ![]() , where the points

, where the points ![]() approach point A more and more closely.

approach point A more and more closely.

Tangent of the slope of the tangent line (slope coefficient)

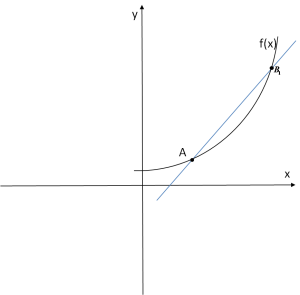

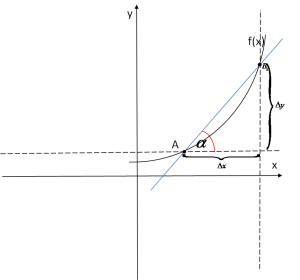

Let us draw one example secant, this time in the coordinate plane:

Let us consider the “inclination” of this secant, that is, a measure of how “steep” the secant rises. As such a measure we take the slope coefficient of the line, which we understand as the tangent of the angle ![]() as shown in the figure:

as shown in the figure:

The angle ![]() is the angle between the line parallel to the OX axis passing through point A and our secant. For simplicity, we will say that it is the angle between the OX axis and the secant (of course it is the same).

is the angle between the line parallel to the OX axis passing through point A and our secant. For simplicity, we will say that it is the angle between the OX axis and the secant (of course it is the same).

The tangent of angle ![]() is perfectly suited to describe how “steep” a line is. The greater the increment of the function values

is perfectly suited to describe how “steep” a line is. The greater the increment of the function values ![]() for the increment of the arguments

for the increment of the arguments ![]() , the greater the angle

, the greater the angle ![]() , and consequently the greater its tangent, which (as we recall from high school) is the ratio of the opposite leg to the adjacent leg, that is:

, and consequently the greater its tangent, which (as we recall from high school) is the ratio of the opposite leg to the adjacent leg, that is:

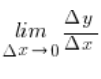

Now imagine drawing successive secants by taking points ![]() closer and closer to point A. For each such secant we obtain a different

closer and closer to point A. For each such secant we obtain a different  , and these values become closer and closer to the exact slope coefficient of the tangent. We can say that the slope coefficient of the tangent equals the limit of such a sequence of slope coefficients of secants as

, and these values become closer and closer to the exact slope coefficient of the tangent. We can say that the slope coefficient of the tangent equals the limit of such a sequence of slope coefficients of secants as ![]() (because the distances from point A to the points

(because the distances from point A to the points ![]() become smaller and smaller):

become smaller and smaller):

Tangent of the slope of the tangent line=

And once we realize that ![]() — that is, that the increment of the function value equals the value of the function at point A plus

— that is, that the increment of the function value equals the value of the function at point A plus ![]() minus the value of the function exactly at point A — we arrive at the conclusion that the value of this tangent (the slope of the tangent line) is exactly equal to the value of the derivative of the function at point A from the previous lecture:

minus the value of the function exactly at point A — we arrive at the conclusion that the value of this tangent (the slope of the tangent line) is exactly equal to the value of the derivative of the function at point A from the previous lecture:

And that in fact, if we agree on the definition…

Definition of the derivative of a function at a point

The derivative of a function at a point is the tangent of the slope of the tangent line to its graph at that point with respect to the OX axis.

We do not need the previous lecture at all; we can define and understand derivatives of functions in this way, without involving any concept of “velocity.” This approach to derivatives (not through limits of average velocities) can be called the “geometric interpretation of the derivative.”

Derivatives at a point as tangents of slopes of curves (examples)

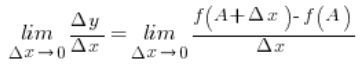

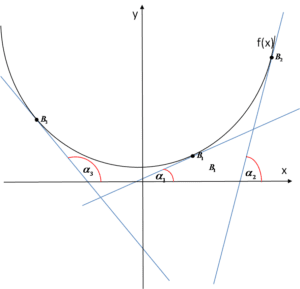

Let us draw several tangents to the curve at different points in the coordinate plane and consider how the tangent of the angle of inclination of these tangents to the graph affects the value of the derivative at those points.

Let us notice that the tangent passing through point ![]() is a decreasing line. The tangents passing through points

is a decreasing line. The tangents passing through points ![]() are increasing lines. However, they differ in their “steepness” — the line passing through point

are increasing lines. However, they differ in their “steepness” — the line passing through point ![]() increases “gently,” while the one passing through

increases “gently,” while the one passing through ![]() is more “steep.” (Notice that this corresponds quite well to the behavior of the curve itself, as we discussed in the previous lecture.)

is more “steep.” (Notice that this corresponds quite well to the behavior of the curve itself, as we discussed in the previous lecture.)

Now let us mark the angles of inclination, respectively ![]() :

:

The angle ![]() is smaller than angle

is smaller than angle ![]() , its tangent is also smaller, therefore the value of the derivative at point

, its tangent is also smaller, therefore the value of the derivative at point ![]() is smaller than the value of the derivative at point

is smaller than the value of the derivative at point ![]() .

.

As for angle ![]() , it is of course greater than angles

, it is of course greater than angles ![]() , but it belongs to the interval

, but it belongs to the interval ![]() , and in this interval the tangent values are negative (this can be checked, for example, on the graph of the function tan x). Therefore the values of the derivative of the function will also be negative, which is reflected in the graph of the tangent — it is a decreasing line. An increment of the argument

, and in this interval the tangent values are negative (this can be checked, for example, on the graph of the function tan x). Therefore the values of the derivative of the function will also be negative, which is reflected in the graph of the tangent — it is a decreasing line. An increment of the argument ![]() corresponds to a decrease (“negative increment” — I hate that expression) of the value

corresponds to a decrease (“negative increment” — I hate that expression) of the value ![]() .

.

END

While writing this post I used…

1. “Differential and Integral Calculus. Volume I.” G.M. Fichtenholz. Ed. 1966.

Click to recall what a derivative understood as velocity is (previous Lecture) <–