Definite Integrals Lecture 2

Topic: Integrability of any continuous function

Summary

In the previous Lecture I defined the definite integral as a certain sum. Recall that definition and think about whether computing definite integrals using it is:

a) Easy

b) Hard

Definition of the definite integral

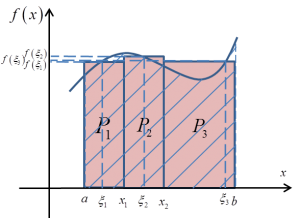

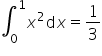

The picture above is a reminder, and the definition went like this:

We have a continuous function ![]() defined on the interval

defined on the interval ![]() . We call its definite integral on this interval the sum:

. We call its definite integral on this interval the sum:

![]() ,

,

where ![]() are the lengths of the subintervals into which the segment

are the lengths of the subintervals into which the segment ![]() is divided, and the points

is divided, and the points ![]() are points inside those subintervals.

are points inside those subintervals.

Provided that (and this is a very important “provided that”):

- the lengths of all subintervals

must tend to 0 as n increases

must tend to 0 as n increases - this sum must be the same for any chosen subintervals

- this sum must be the same for any chosen points

inside the subintervals

inside the subintervals

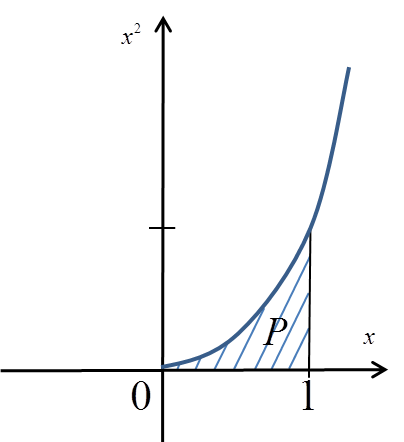

Pay attention to these last two conditions. Let us say we want to compute – using the definition – a very simple definite integral:

On the graph this integral would be the shaded area below:

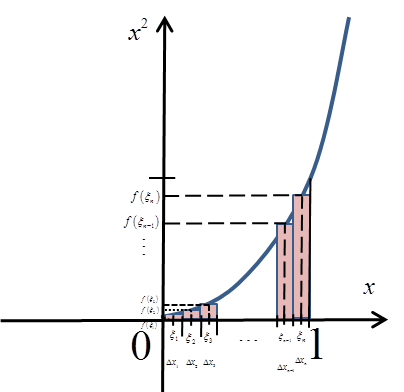

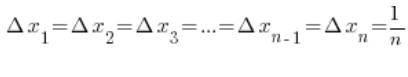

To compute this area from the definition, without using any additional theorems, it would NOT be enough, for example, to divide the segment ![]() into

into ![]() EQUAL subintervals (each would have length:

EQUAL subintervals (each would have length: ![]() ):

):

![Pole pod funkcją x^2 w granicach od 0 do 1 z zaznaczonym podziałem przedziału [0,1] Pole pod funkcją x^2 w granicach od 0 do 1 z zaznaczonym podziałem przedziału [0,1]](https://blog.etrapez.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2012/02/Obraz31.png)

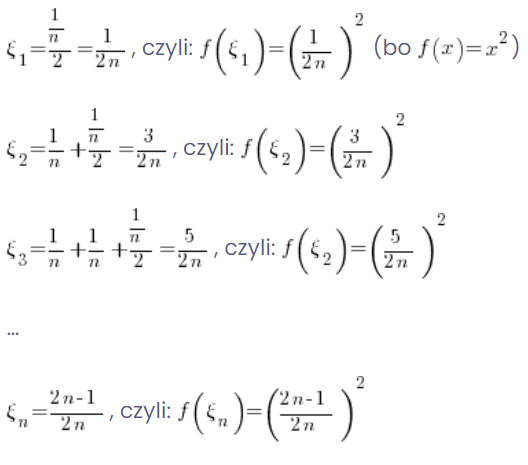

It is NOT ENOUGH now to choose the points ![]() for example exactly in the middle of those subintervals:

for example exactly in the middle of those subintervals:

It is NOT ENOUGH to compute the resulting integral sum (that is, geometrically speaking, to sum the areas of those rectangles):

(we divide the segment of length 1 into

(we divide the segment of length 1 into ![]() equal parts)

equal parts)

So my sum will be equal to:

![]()

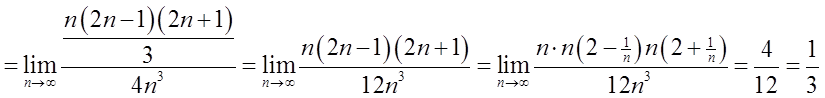

Using the formula for the sum of squares of the first n odd numbers (yes, such a thing exists):

But all of this is still NOT ENOUGH (even though of course the result is correct and the area really is equal to ![]() ) to compute from the definition the integral:

) to compute from the definition the integral:

Why?

After all:

- I divided the segment

into 'n’ equal subintervals

into 'n’ equal subintervals - I chose, in the middle of each such subinterval, the point

- I computed the sum of the lengths of those subintervals multiplied by the value of the function at the points

(i.e. the areas of the rectangles)

(i.e. the areas of the rectangles) - This sum turned out to be finite (

), and the lengths of the 'n’ equal subintervals were infinitely small as 'n’ tended to infinity

), and the lengths of the 'n’ equal subintervals were infinitely small as 'n’ tended to infinity

So why can I not (yet) conclude that:

?

Unfortunately, it is because in the very definition of the definite integral there is the condition that yes, the integral sum should be convergent (and it is), but besides that it is also written there that it must converge to one and the same number for an arbitrary partition of the interval ![]() and for an arbitrary choice of points

and for an arbitrary choice of points ![]() .

.

What I did, on the other hand, was only to show that the sum converges to ![]() for one partition chosen by me, with subintervals

for one partition chosen by me, with subintervals ![]() (it happened to be a partition into equal parts) and for one method chosen by me for selecting the points

(it happened to be a partition into equal parts) and for one method chosen by me for selecting the points ![]() (I chose them exactly in the middle of the subintervals

(I chose them exactly in the middle of the subintervals ![]() ).

).

This does not yet mean that:

To prove this (on the grounds of the pure, very pure definition alone) I would have to somehow show that for all ways of partitioning the segment ![]() into subintervals

into subintervals ![]() and for all possible choices of intermediate points

and for all possible choices of intermediate points ![]() , always and in every case the integral sum is equal to

, always and in every case the integral sum is equal to ![]() .

.

Do you already know the answer to the test question from the beginning of the lecture:

whether computing definite integrals using it is:

a) Easy

b) Hard

?

Of course, I will not even try to tackle such a suicide mission. I need something more, some additional artillery. It will be a new theorem (so, with a heavy heart, I am already going beyond the pure definition).

Theorem on the integrability of a continuous function

Every function continuous on the interval

is integrable on that interval.

A theorem as simple as a club, right? But what exactly follows from it, and how can it help me compute from the definition the integral:

?

?

Let me rewrite it in other words and it will become clear by itself:

If the function

is continuous on the interval

, then for any partition of the segment

into subintervals

and for any choice of intermediate points

its integral sum converges to the same number.

Right? Because that is exactly the meaning of the word “integrable”. And the logical conclusion from the theorem above is:

- If the function is continuous on the interval

- If I have found one of the possible partitions into subintervals

and points

and points  , for which the integral sum converges to some number,

, for which the integral sum converges to some number,

then:

By the theorem on the integrability of a continuous function, for every other partition every “other” integral sum will converge to the same number (because if it is continuous, then for any partition it converges to the same number)!

So – having a continuous function – you can compute its integral sum for any partition chosen by you (e.g. a partition into equal subintervals and intermediate points in the middle), cite the theorem on the integrability of a continuous function, and in this way determine (finally) the definite integral from the definition.

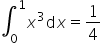

So, returning to my example of the integral:

Everything was fine and all calculations were valid; however, at the end one should still add:

By the theorem on the integrability of a continuous function (the function ![]() is of course continuous on the interval

is of course continuous on the interval ![]() ), from the fact that the integral sum for the partition chosen by me with subintervals

), from the fact that the integral sum for the partition chosen by me with subintervals ![]() and points

and points ![]() came out equal to

came out equal to ![]() it follows that for any other partition it is also equal to

it follows that for any other partition it is also equal to ![]() , and therefore:

, and therefore:

I will postpone the proof of the theorem on the integrability of a continuous function for another time.

Now I will show you two other examples of computing a definite integral from the definition.

Example 2

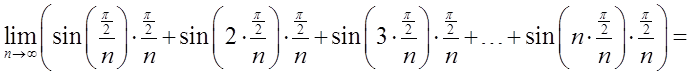

Compute from the definition:

.

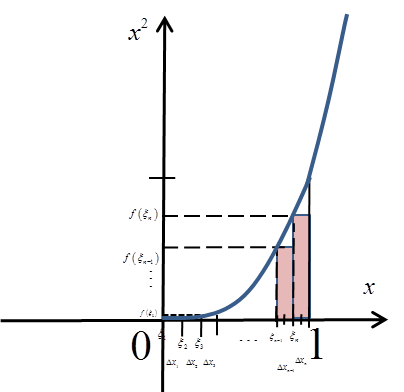

I divide the segment ![]() into n equal parts and choose the points

into n equal parts and choose the points ![]() exactly at the beginning of each subinterval

exactly at the beginning of each subinterval ![]() :

:

So for the function ![]() I have:

I have:

So my integral sum will be equal to:

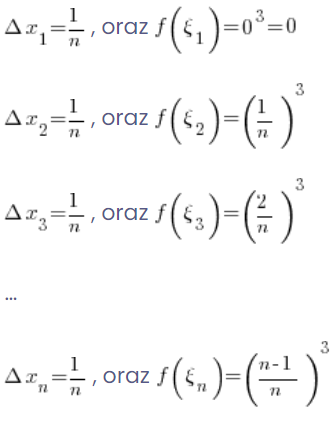

![]()

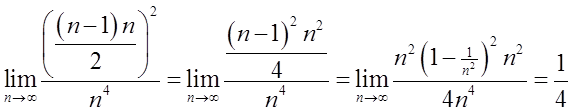

I use the formula for the sum of cubes of consecutive natural numbers ( ), modified because I have n-1 terms:

), modified because I have n-1 terms:

The function ![]() is continuous on the interval

is continuous on the interval ![]() .

.

By the theorem on the integrability of a continuous function:

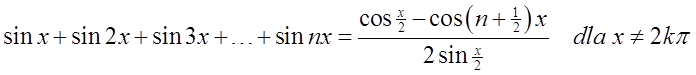

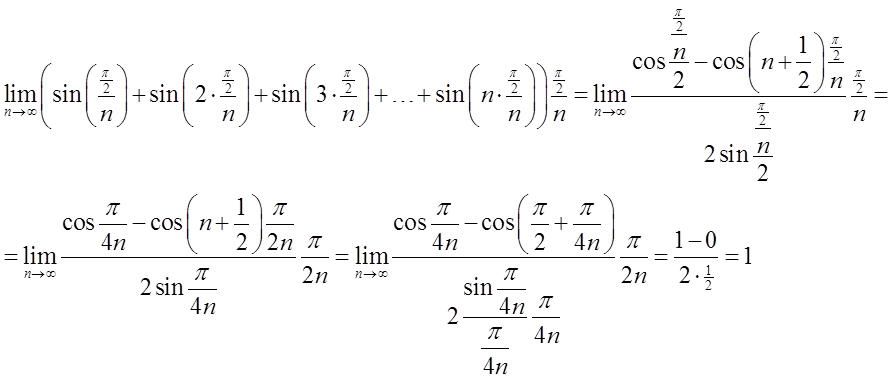

Example 3

Compute from the definition:

.

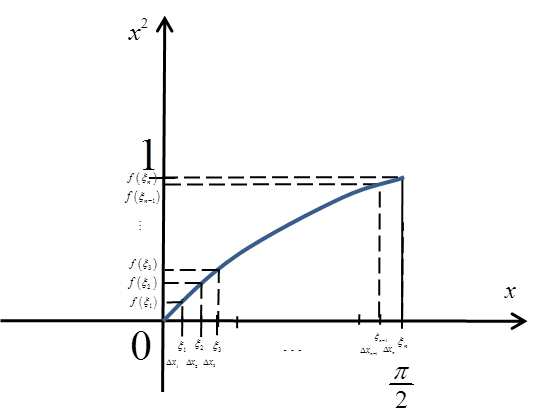

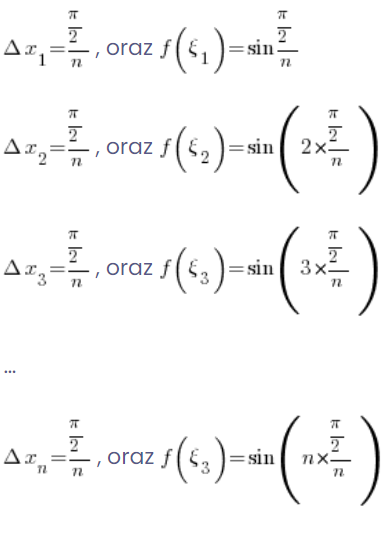

I divide the segment ![]() into n equal parts and choose the points

into n equal parts and choose the points ![]() at the end of each subinterval

at the end of each subinterval ![]() :

:

So for the function ![]() I have:

I have:

So my integral sum will be equal to:

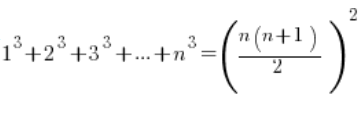

It is of course difficult, but the following formula will be helpful (it can be proved by induction):

After using this formula, I will have:

Therefore, by the theorem on the integrability of a continuous function:

THE END

While writing this post I used…

1. „Differential and Integral Calculus. Volume II.” G.M. Fichtenholz. Ed. 1966.

Click to review the definition of the definite integral (previous Lecture) <–

Click here to return to the page with lectures on definite integrals

.

. .

.